Paradise Lost & Found

Do you have a place in your mind that represents paradise to you? Although I lived on Oahu for a short time when I was quite young, Hawaii occupies that place for me. Hawaii holds such a dear place in my heart and mind but, it’s an image forged within the mind of a child; and so I wonder if the place that the little girl remembers truly exists? Yet I have this fear that if I went back, I would never leave.

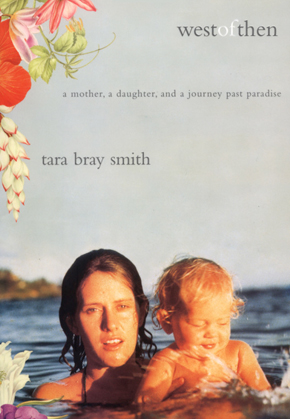

Several years ago, I read West of Then by Tara Bray Smith when it was first published. It is the story of a mother and daughter’s journey in that Hawaiian paradise; a story so remarkable and so profound that it became etched in my mind, so much so that I wanted to talk to the woman behind the book. I am so honored to say that this week’s culture piece is an interview with this fantastic author, where she talks writing, family and of course, our shared adoration of magical Hawaii.

danapop (dp) Writing is quite isolating, how do you find balance in that?

Tara Bray Smith (tbs) I encountered the word “isolatoes” in Moby-Dick, when I was writing West of Then. It refers to sailors on the Pequod, Polynesians like Queequeg, but also existential islanders, “not acknowledging the common continent of men.” I was drawn to the concept because I was writing a book about Hawaii but I think I was also discovering that to write is to be a willing isolato. I live in Germany now, far from where I grew up—even far from New York, where I spent my late twenties and early thirties. My husband travels a lot and I’m alone often. This does not apply to all writers (I seem to remember Joyce writing on a hotel bed, family around). But even in my empty house I shut the door to the room where I write. There isn’t much balance possible. You’re either in there, doing it, or you’re feeling guilty.

dp Did you experience some backlash or discomfort from your family after West of Then was published?

tbs I did. A few family members confronted me about feeling exposed and I’m glad they did. It wasn’t until the book was in galleys that I understood how powerful the act of documentation, writing, is. I find this remarkable and wonderful, that humans can be moved to action by the abstract expression of thought through words on a page. But it is also a terrible responsibility. Until then I had been doing private, emotional, aesthetic work. When the book was published I was faced with the weight of what I had written, its life outside of me. My mother said something regarding some incident I had narrated, she said, “Well, it’s in the book. It had to be have happened that way.” It was as if I had taken authorship of her own life from her.

dp Does your mother still live in Hawaii? What’s your relationship like today? Your sisters?

tbs My mother and one of my sisters lives in Hawaii, the other two are in California. We are a family, with the same ups and downs as any family, I guess, though I think I did break something with the book I wrote. Maybe not something in them (though I think I did hurt my mother), but in the role I had played till then. As a writer you want to observe life as it happens, then scurry off and write about it; once that scheme is revealed, people don’t trust you in the same way. Nor should they. The genre is tricky. There’s a hunger for “reality” in our age and a flouting of privacy. I did this. I’m writing a novel now and I wonder how I will see these questions when I am on the other side of something imaginative.

dp You’ve lived in some pretty amazing places – Honolulu, NYC and now Berlin…how does where you live influence your writing?

tbs Well, it keeps me an isolato! I guess finally ending up here, as far from where I grew up as I could get and stay on the planet, I saw that I had spent the first part of my adulthood defining my separation. I’m away now. I have accepted the fact that I will be an expat American writer: I sort of felt like one even in New York, though the sentiment seems disingenuous now, from an hour west of Poland.

The moves have made me interested in what has constituted American fiction during the modern period: much of it variations on the immigrant story. I haven’t figured out what my perspective on this is yet, as someone who has moved away, not toward, but I guess I’m working on it.

dp What do you miss about Hawaii? How often do you go back?

tbs I miss everything. I miss the smell, the ocean, trees that I know the names of, a green that I recognize, the sand, rain, the way people talk, the music, the mountains. Last year I went back four times (!), but this year I don’t think I’ll get back. And of course you can never get back to the place you exactly knew, because that place is in your head.

dp How did you compile all the research for the book? Your historical accounts are fascinating – Cook Islands, etc., how much of it did you want to include? I felt as the reader it made the emotional stuff a bit easier to deal with, did you come to that same conclusion as the author?

tbs I spent several years reading and researching and about eight months in Hawaii. I felt that the story, because it was true, deserved to be properly situated in a truthful history. That’s an interesting way to see it: that it also emotionally contextualized the drama (trauma?). Mostly I was just very confused, and I think the research was a way of starting at the beginning, so that I might be able to understand.

dp One of my favorite images in your book really is this ongoing dualism of such a rich, lush paradise filled with profitable sugarcane crops, against the stark reality of your family dynamic. How did you decide to weave that in? Were they both there the entire time?

tbs Thank you. Now that I can look at my childhood with a measure of spatial and emotional distance, I can see that it must have been very confusing for me, as a kid, to enter this world of (relative) privilege that my great-grandparents hung on to, with the plantation and the silver, etc.—of course that was from a child’s perspective, it was really a dusty, country life. But I had those cousins that were at Choate, and the stories about Berkeley and Aunt Isabel and here my mom was, on the Honolulu bus, bleeding, or here we were in a battered women’s shelter in Houston, or here we were stealing steaks from the grocery store. You normalize things as a kid, you make them all part of the same story. I guess the book was untangling the strands.

dp You published a book young adult fiction post West of Then, how did the writing process of Betwixt compare? Do you like writing for that particular audience?

tbs I did like it. Young readers are demonstrative and really care—I get letters from them talking much more about their visceral like or dislike of the book. This kind of gut reaction is what I always had for books and I still do for what we term literary fiction. I would like to write for adults in the way that makes you feel something—scared, sad, awed, turned-on, angry. My favorite authors do this. You put the book down and you stare out the window and just go, wow.

dp What do you hope people gain by reading West of Then?

tbs Good question—I’ve never been asked that. I guess that I would like the story to stand as a statement of the validity of its own narrative. That the stories we use to guide our lives, to make our decisions, to give us a path to follow—the bootstrap tale was always my favorite–are often wrong or so simplistic as to be impossible. Complication is life’s point: loss is also our inheritance. How do you tack through a storm? I don’t know anything about sailing—maybe you don’t “tack”. But I guess I was trying to put down how these related stories happened, in this place, at this time, to these people.

dp Describe the process a bit from your life’s story and your experience to then writing and it getting the work published. Did you set out with the intention that it would be a book?

tbs I started writing stories about my mother in college, some of which became the basis for chapters in the book. After teaching high school English for four years after college in Lake Forest, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago, I decided I wanted to try to write. I entered a nonfiction MFA program at Columbia because I had been reading a lot of essays at the time and I liked the freshness of the genre. What I had been obsessed by till then were these stories about my mother, and they were true, so I decided that this was how I would write. The beginning of my MFA was really hard; I had no training and a lot of what I wrote in the program was a disjointed mess. I think the book still suffers from structural confusion, but I guess the six years between starting the program and getting the book published, was a process of trying to figure out what I was trying to say.

dp How does your husband support your writing process? He is the famed photographer, Thomas Struth, correct?

tbs What is an artist? I have no idea, but I am learning. Thomas supports me in every way—he shares his experiences with me, he talks to me about his questions and decisions and concerns; he is a mature working artist and simply to have a model like this close to me in my life helps me. I am shy about sharing my work before it’s “ready,” but we talk about it and he will really challenge me to get beyond a kind of natural haziness I have at the beginning.

dp Your relationship with your father and stepmother is another story in the book that added such an amazing layer. How did they help shape you into the person you are today?

tbs My father passed away a little more than two years ago and I miss him every day. He was surfing and probably had a heart attack, in any case, it was sudden. It’s hard for me to explain the shock and loss I have felt after my father’s death. I think he’s the reason I’m a writer. He used to read paperbacks by the foot, one every few days. His mother he said was the same way. Was I writing to him? To her? She committed suicide when I was five. I don’t know. Maybe I still am.

My stepmother is a wonderful, loving mother and friend. She was ambitious for me, which I have always appreciated. Our relationship is also strong proof to me about what constitutes a family bond: how blood, gender, age is all less important than love, caring, authority, trust.

dp I imagine it to be a bit strange to not see the ocean when you’ve grown up around it – is it?

tbs AAAAH! There are a few canals here in Berlin and some lakes – but when I go to Hamburg I can immediately smell the ocean and sniff the air like a dog.

dp What are you currently working on?

tbs A novel set in Düsseldorf, where I lived when I first moved to Germany. Sort of an autobiographical premise that takes a scientific turn. I just started.

dp What does your writing space look like?

tbs It’s a species of triangle at the back of the apartment, and its sole, slim window looks out onto a linden tree. We’re on the fourth floor at the treetop. Yellow birds fly between the branches. When it sways I feel like I’m on a ship, looking out into a green sea.

dp How do you think this publishing industry has changed since West of Then came out? Do you think blogs have hurt or helped the writing and publishing process (or maybe neither)?

tbs I love blogs and read them all the time. I think it’s too soon to tell how all of this will change the publishing industry, and of course I worry about the fate of newspapers, which I think are crucial for the accurate reporting of the world around us and for a functioning democracy. The one thing I would say that you often don’t deal with in a blog situation is the many levels of fact-checking and editorial input that you have in the MSM. Though there are exceptions on both sides, and I imagine we’ll find a way to make this work for both writers, publishers, and readers. I don’t think people give credence enough, however, to how durable the written word is, how supple, entertaining, necessary (in the truest sense). Language is how we think, and writing is how we challenge and refine that thinking and sometimes, make it eternal.